Written by Guy Peploe, 1998

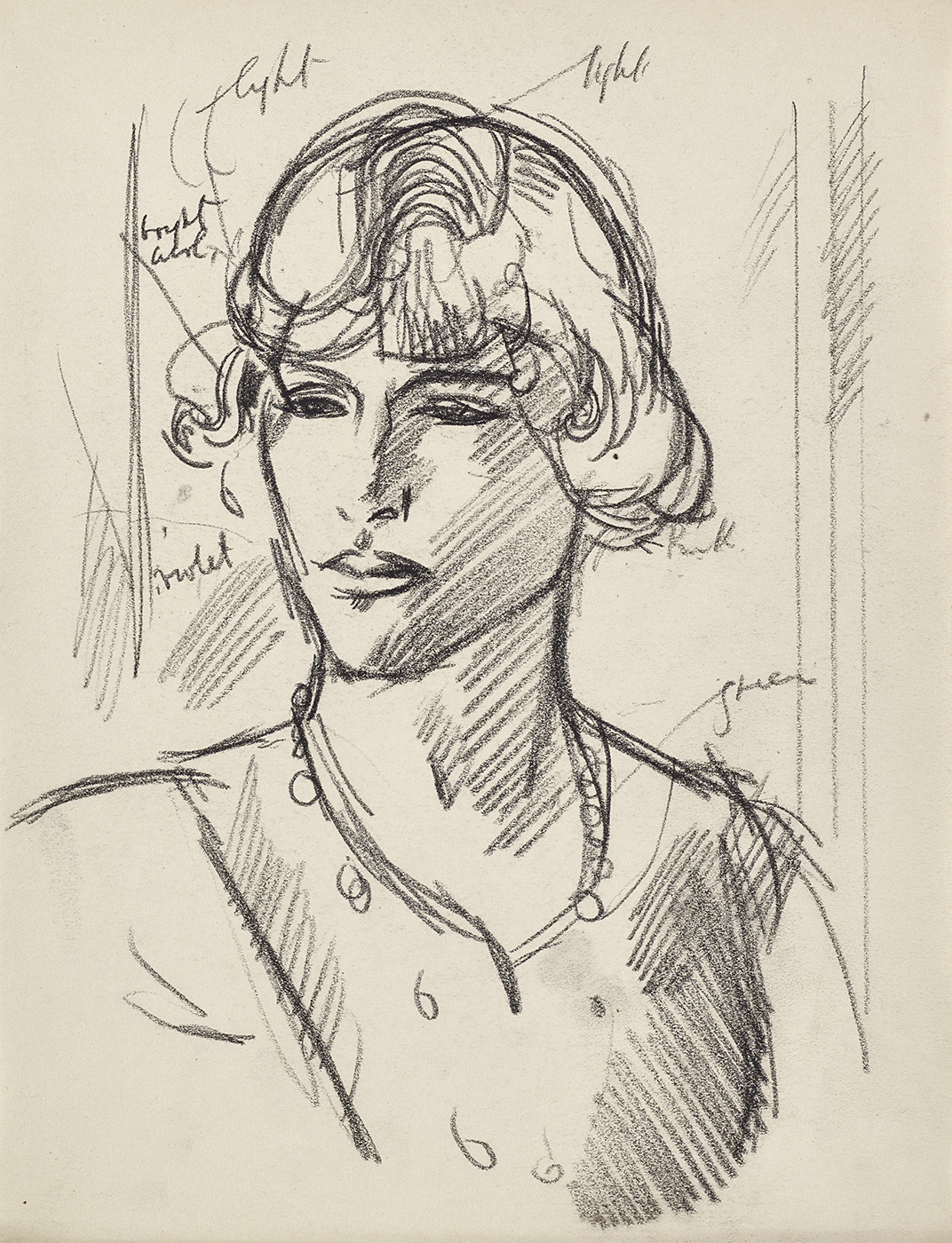

John Duncan Fergusson drew women every working day of his long, productive life.

They were not his only subject, but his most important: Rhythm, and Les Eus being two works of sufficient stature to secure his reputation alone. But his quotidian dedication, his thousands of sketches are testament to a life devoted to women. And they are not passive, the gaze is not averted; instead they are celebrated as equals, potential is unbounded and the artist’s respect for his subject is palpable, their participation in the act of making a work of art an assertion of equality. This is not to say the sexual relationship, or its potential, is absent; rather the making of art is always primary, the making of love secondary. His status as an artist, a genius with matinee idol looks, was not a ruse to seduce his models; nor was his dismissal of convention, of bourgeois mores a ruse de geurre. Art was above all else and its pursuit, or worship allowed no compromise. I have often asserted in lectures, perhaps to check my audience is awake, that Fergusson’s women took their clothes off in around 1911 and never put them on again. It is perhaps also true that his draped model is more sexually charged than his life model: much of the apparent character of the sitter is in her dress; nude she may be sexualised but she may also have been stripped of her individuality.

Guy PeploeI have often asserted in lectures, perhaps to check my audience is awake, that Fergusson's women took their clothes off in around 1911 and never put them on again.

From 1913 Fergusson was with Margaret Morris who shared his absolute dedication to art. It is no coincidence that the convention of family was dismissed along with much else by both Fergus and Meg. Their relationship may well have been open and Fergus continued to sleep with many of his models, a natural, open act of little consequence. Meg would have understood this perfectly: not complicit, but disinterested. She herself had an affair with the writer John Galsworthy in the twenties. The names of some models: Ida Rubenstein, Janice, London or the striking asymmetry of the face of Kate Dillon in Rose Rhythm, 1916 seem personal, beyond the mere urge to paint and the sexual element, the stimulation to the creative impulse, is no doubt important, as it was for Picasso and Lucian Freud. However the most sexually charged works are from the early period. The cupid’s bow mouth, high colour and direct challenge in the eyes of Jean McConnachie, one of his first models, and unusually by his own account conquests, is highly charged, images of a woman asserting her own sexual choice, an equal in the painting and the proceeding sexual act.

In Paris Fergusson believed himself spiritually at home.

In Paris Fergusson believed himself spiritually at home in the demimonde of the fin de siècle amongst circus and music-hall performers; brothels catering for clients from the future Edward VII down – the artists, poets, refugees and workers who made up cafe society in Montmartre and Montparnasse. The freedom and license of the great city was in contrast to a buttoned-up Edinburgh still subject to the proscriptions of the Sabbath from which Fergusson was pleased to have escaped and urged his friend Peploe to join him from 1907. The exoticism of paintings such as Voiles Indiennes, and the cafe paintings of 1908/9 evoke Maupassant, Flaubert and Huismans and are testament to how fully Fergusson embraced this, his world.

View more work by J D Fergusson here

Guy PeploeIt was to here that the young, recently arrived Picasso made a visit, to meet this enigmatic Scot, the paragon of bohemian living...

In these earlier years his lover was the American painter Anne Estelle Rice who with her friend Elizabeth Dryden had come from Philadelphia to draw the Paris fashions for American magazines and her broad, handsome face and fine carriage appear in many drawings, a kindred spirit assisting in his grand bohemian project. A visitor recalled his studio in Boulevard Edgar Quinet decorated in white; white painted floorboards, furnished with a models throne and wicker chair and table bearing the only object in the room: a box of long, purple-headed matches. Fergusson presiding, Mephistophelean with his chiselled features, side parting and three-piece worsted suit. It was to here that the young, recently arrived Picasso made a visit, to meet this enigmatic Scot, the paragon of bohemian living, running his art school La Palette in the quartier; the young Spaniard left a drawing which Fergusson would incorporate into his graphic identity. As art editor of the short lived but influential periodical Rhythm, Fergusson illustrated work by Picasso and Derain as well as Rice and Peploe. The American, London based publisher Raymond Drey would take up with Rice as Fergusson’s attention moved to Morris in 1913.

Margaret Morris was a choreographer, dancer and dance-school entrepreneur who would be his match and life-long partner, sharing their life in Cap d’Antibes – escaping to London in 1914 – with her summer schools in France and Wales; to Glasgow, escaping France again in 1939. Here, his own painting, for the first time undermined by formula, his women more archetypal than real, began to decline, but his generosity to the young and his belief in the potential of his protégées, including a sixteen-year old Pat Douthwaite, was undiminished, his Feminist credentials fulfilled.